The Libero: The Forgotten Position in Football

Football philosophy has evolved and changed over the years, transforming the shape of the game since 1930. Thirty or forty years ago, we would have watched an elegant and intelligent player who was skilled at controlling the ball and bringing it out, positioned behind his team’s defenders. Free from traditional man-to-man marking duties, he would cover through balls behind his team’s defenders while providing numerical superiority in the first third of the pitch. This player was called the libero.

Karl Rappan, an Austrian-Swiss player and coach, is considered the first to invent the concept of the libero – an Italian word meaning “free.” In football terms, it refers to an extra player positioned between the center-backs who can advance with the ball to join the midfield and attack.

Development in Italy and Germany

The use of this position was concentrated in two countries with different, perhaps even contradictory, football cultures: Italy and Germany.

This system didn’t gain popularity until it was adopted and developed in Italy by coaches Nereo Rocco with Triestina and Gipo Viani with Salernitana. With the emergence of Catenaccio in the 1960s, Helenio Herrera gave the libero more defensive roles. His main task was to support the center-backs and provide numerical superiority against fast players. The libero was the true beginning of the Italian defensive legend.

Armando Picchi, Inter’s captain during this period, is considered the first world-class libero. He was the safety valve in Inter’s Catenaccio (an Italian word meaning “door bolt”), though some consider Armando the most negative (defensive) use of the libero position.

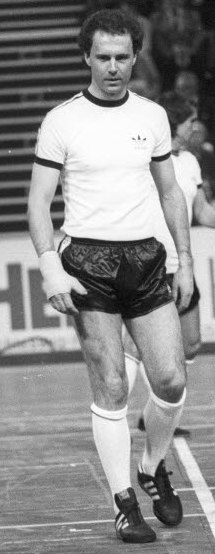

The Golden Era: Franz Beckenbauer

image source here

The golden period for this position was in the 1970s with the genius Franz Beckenbauer, who is considered the most famous and perhaps the best to play in this position. He had the authority and ability to advance and progress with the ball from the defensive area to the opponent’s penalty box to create and score goals, which he regularly did. The Kaiser led both Bayern and West Germany to unprecedented success in the 1970s and is considered the most positive (attacking) use of the libero position.

The Complete Libero: Gaetano Scirea

After Beckenbauer, another genius carried the libero torch – Gaetano Scirea, but he was a different type of libero. He combined Armando Picchi’s defensive qualities with Beckenbauer’s attacking capabilities, creating a wonderful mixture of both. Some consider him the best Italian defender of all time. He wasn’t just an exceptional defender but distinguished himself with his calmness in handling the ball, precise long passes, and distinctive runs with the ball. Scirea represents the balanced use of this position.

At that time, there was another libero in Milan – Franco Baresi, distinguished by his ability to read the game and his quick runs with the ball similar to strikers’ runs. Anyone who saw Baresi advancing with the ball would think he was a playmaker or striker. This was all in addition to his exceptional defensive talent. Baresi’s role as libero ended with the arrival of Arrigo Sacchi, who adopted playing with four defenders in the back line.

German Excellence Continues

Next came another German, Lothar Matthäus, who started as a box-to-box midfielder at Borussia Mönchengladbach, then as a playmaker at Inter, before coach Vogts decided to move him back to the libero position. He became one of the most successful players in the libero role in the game’s history, alongside his German teammate Matthias Sammer, another pillar of Borussia Dortmund who also started as a midfielder before converting to libero and achieving brilliant success in this position. (Beckenbauer, Matthäus, and Sammer all won the Ballon d’Or).

The common factor among all who occupied this position was that they were all historical leaders of their teams. Leadership personality was the most prominent characteristic of a libero player.

The Decline of the Libero

One of the drawbacks of relying on a libero player in the team is the numerical shortage in midfield. This shortage led many coaches to move away from this idea. With his dislike for player specialization on the pitch, Arrigo Sacchi was the first to end the libero’s role as a cornerstone in Italian playing style during his tenure with Milan in the late 1980s. He changed the traditional Italian defensive method of three players (two fixed center-backs with a free player – the libero) to playing with a 4-4-2 formation.

Over time, the appearance of the libero position declined in favor of the defensive midfielder position, or what’s called the “regista” – a midfielder positioned in front of the center-backs instead of behind them, as was the libero’s function.

Some attribute the extinction of the libero to the offside rule and the negative role the libero plays in breaking the offside trap. Others attribute it to the increased reliance on high pressing in modern football, which doesn’t give the libero enough time to pass balls as he used to. However, this reason isn’t very convincing because it would mean that any current playmaker doesn’t have enough time to pass the ball properly, which is completely incorrect.

The clearest reason for not relying on a libero player remains the numerical shortage he causes in midfield when the ball is with the opponent, especially since the libero system and Catenaccio were often used by technically weaker teams, meaning they were less capable of possession and controlling the midfield.

Modern Evolution

Additionally, the late 1990s and early 2000s saw increased reliance on the fullback position, meaning there were defenders who would advance with the ball. If we added the libero to them, the defense became very exposed with three players advancing from it, or you had to keep the libero while not relying on attacking fullbacks, which was the most important weapon of that period. Gradually, this position disappeared and was compensated by other roles for the remaining positions.

In addition to the regista, the libero’s roles were compensated by relying on the ball-playing defender – a fixed center-back who performs all his defensive duties but is distinguished by his ability to play long and through passes. He can be considered a libero but without the authority to advance with the ball whenever he wants. There are many current defenders who excel in this role, such as David Luiz, Jérôme Boateng, Sergio Ramos, and especially Leonardo Bonucci, who played a very similar role to the libero with coach Antonio Conte in Italy and Juventus when he would create play from the back, positioned between the center-backs.

The closest use of a role “similar” to the libero in modern football was with Italy when coach Cesare Prandelli decided to include Daniele De Rossi as a defender between Bonucci and Chiellini in Euro 2012 against Spain in the group stage. This was a counter-tactic to Spain coach Del Bosque’s use of Cesc Fàbregas as a false striker, which seemed aimed at restricting regista Andrea Pirlo. Daniele here freed Pirlo, who advanced more in midfield, and De Rossi delivered one of his best performances ever.

Conclusion

With the end of the last century, we witnessed the disappearance of the libero position, just as we later saw the decline of the traditional number 10 role, and perhaps we’ll soon witness the disappearance of the traditional number 9. But what’s certain is that football will remain a game of ideas off the pitch before being a game of feet on it, and will remain in constant motion of change with brave coaches capable of innovation and thinking outside the box.